During black history month, we celebrate black cultures and recognize black historical figures. In our recent past, however, black history has been the history we have forgotten to remember and remember to forget. Often this history wasn’t well recorded, and since researchers generally weren’t looking for this information, it wasn’t found. Even if it was stumbled upon, it was often disregarded. Over the past decade, there has been a strong movement to encourage history organizations to tell the untold stories of marginalized communities. This movement has manifested itself in focused funding, prioritized research, and increased educational opportunities. This effort has expressed itself on the East End in a more concentrated push to tell the untold stories of our local marginalized communities. In celebration of Black History Month, I would like to recognize these groups whose hard work and efforts have done so much to make local Black history come alive.

I want to start with one of the most local efforts, the North Fork Project. With the encouragement of Steve Wick, two-and-a-half years ago, three local historians got together to tackle a subject that has not previously been considered important: the history of slavery on the North Fork. In that time, the researchers, Riverhead historian Richard Wines; Southold Town historian Amy Folk; and Sandi Brewster Walker, uncovered and pieced together a great deal of information. Individually they had done some research, but their collaborative efforts have expanded the breadth of knowledge on the subject. The group has shared its findings with the community through newspaper articles and a meeting last November. The database of their findings will now be merged with that of the next group I want to mention: The Plain Sight Project.

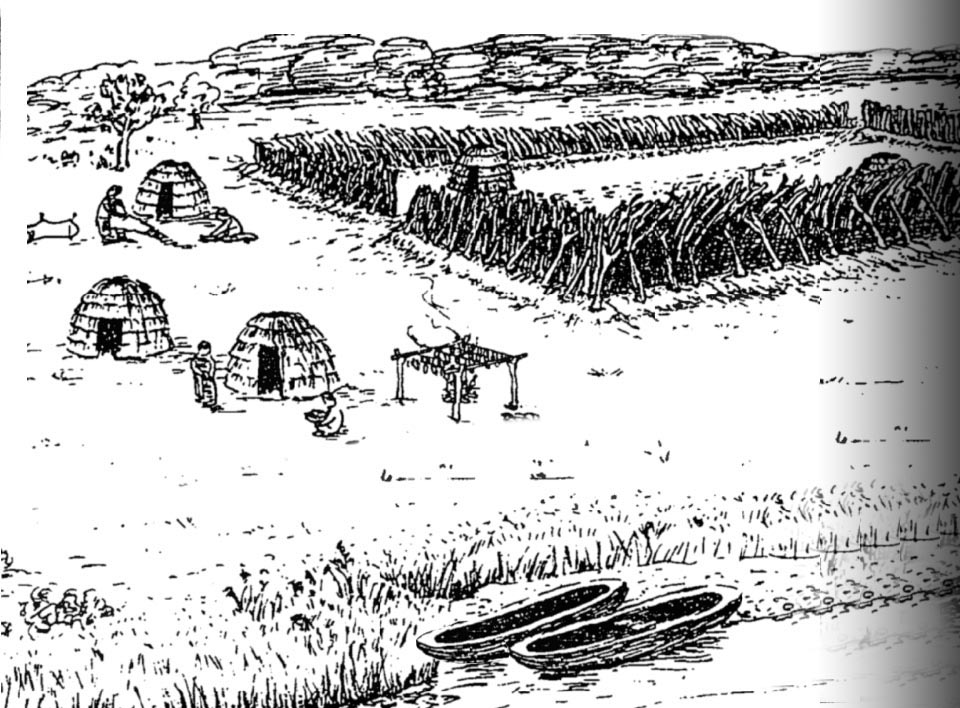

The Plain Sight Project works to restore the stories of enslaved persons to their rightful place in American history. Donnamarie Barnes, the curator of historic Sylvester Manor on Shelter Island, and David Rattray, the East Hampton Star newspaper editor, co-founded the project in 2016. At the time, they only had two known individuals with confirmed identities. This has grown to more than 770 people. The next step for the Plain Sight Project is creating a template with which groups in other parts of the Upper Mid-Atlantic, New York State, and New England can comb their own communities’ archives for enslaved persons, with the goal of creating a granular national database that can be searched by individuals and be used to understand the relative presence and location of enslaved persons in the region through time. It is hoped that the amassed data will encourage the managers of historic properties and public officials to recognize the presence and contributions of enslaved persons in Eastern Long Island’s colonial period.

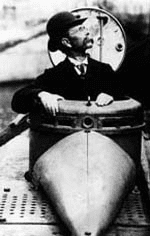

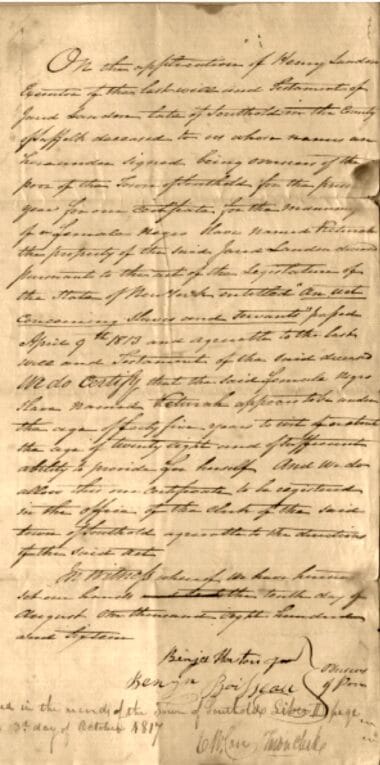

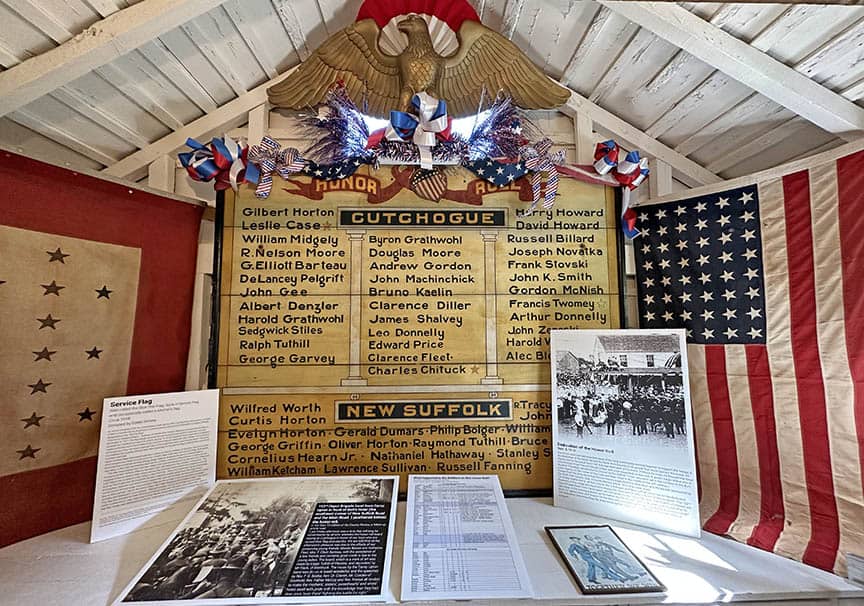

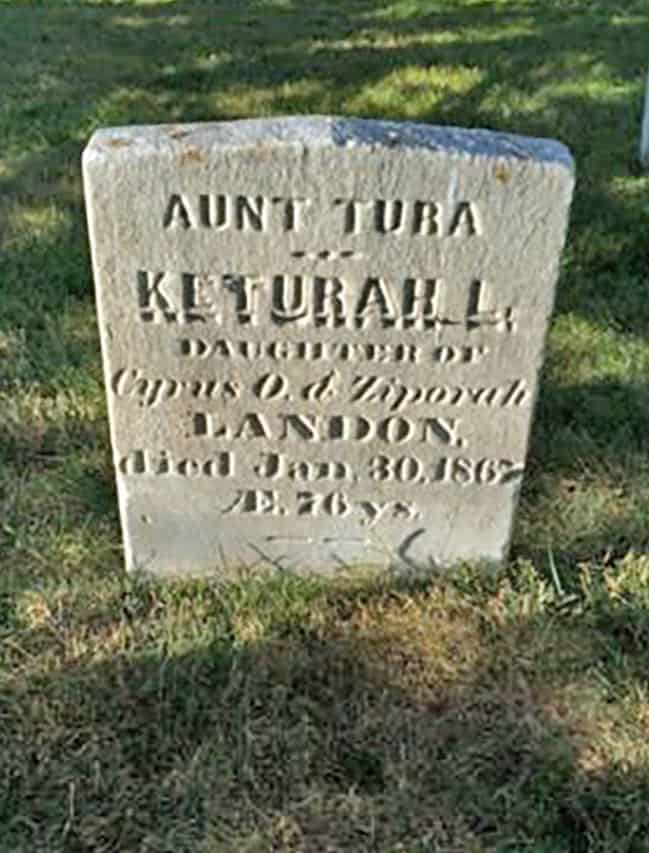

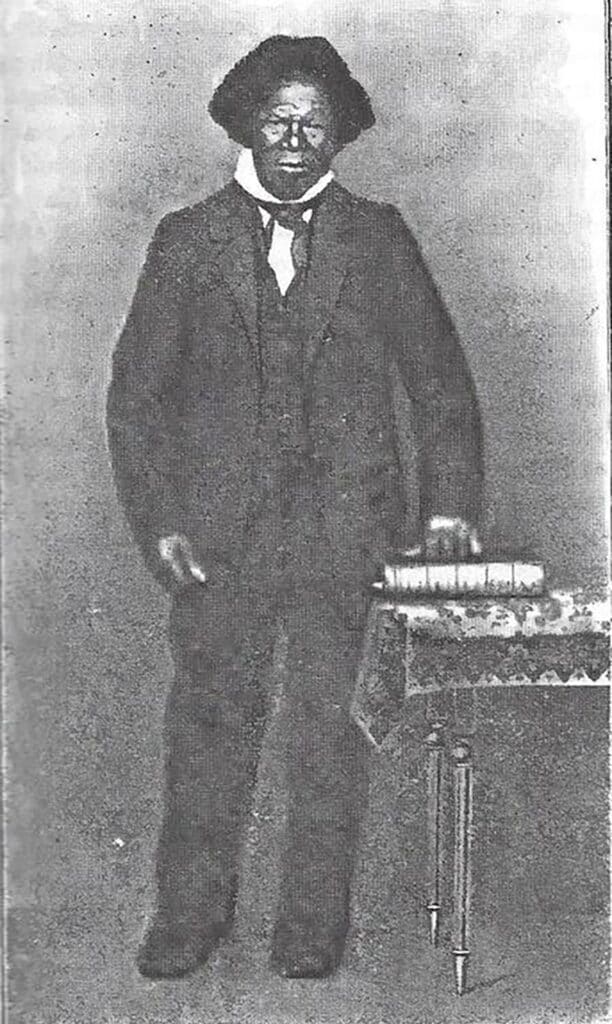

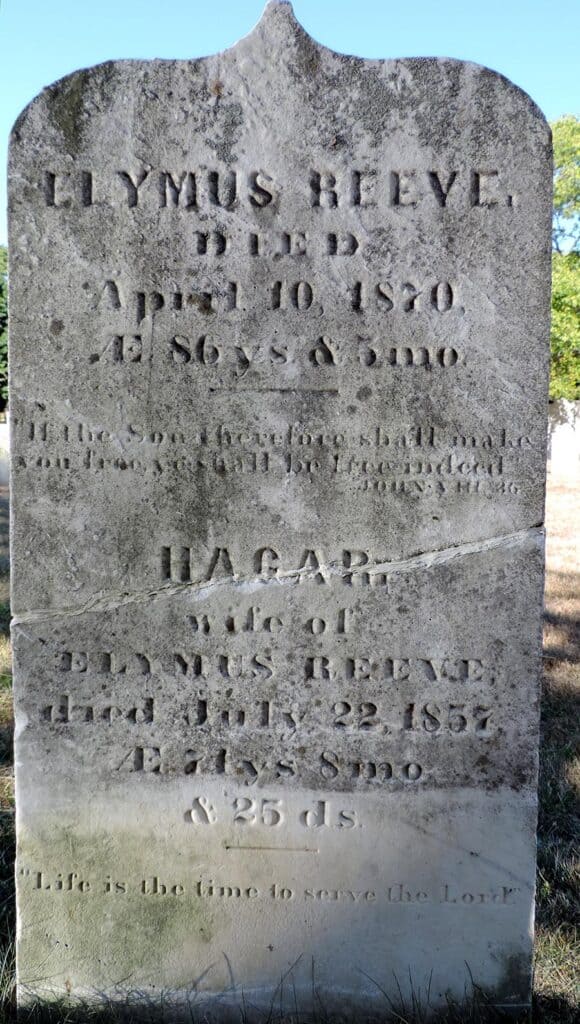

The work these groups have done has already changed how many local history organizations such as ours are thinking about how their findings will affect our narratives and how we can include their stories in the stories we are currently telling. Instead of just mentioning that some of the early owners of the Old House were enslavers, we can say the name of Keturah and tell the story of her manumission (release from slavery) from her enslaver, Jared Landon (one of the owners of the Old House, just after the Revolutionary War), just as we have said his name and told his stories. One of the most fully fleshed-out stories of an enslaved person is that of Elymus Reeve and his family, who are buried in the Cutchogue Burial Ground. He has a very interesting story to tell, and his descendants went on to make great contributions to America. Lymas Reeve’s youngest son, John B. Reeve, graduated from Columbia University and from the Union Theological Seminary and taught at Howard University. He earned a doctorate in divinity and was named pastor of a Presbyterian church in Philadelphia. His neice, Josephine Yates, became a prominent lecturer and was active in the National Association of Women’s clubs.

So, if we are so inclined to celebrate Black History month, it can sometimes be difficult to do so accurately and meaningfully. Applauding and supporting these hard-working groups and incorporating the histories they are discovering into the stories we have been telling about the past seems a very relevant and meaningful way to celebrate Black History month and honor those that have come before us.