A Victorian Christmas

As part of our tree lighting and Holiday event on Dec. 3, we interpreted three of our historic buildings to represent Christmas during that period. The Old House, a colonial Christmas, the Wickham House, a Victorian Christmas, and the Schoolhouse, a mid-century Christmas. We will be releasing three consecutive blogs which will talk about each one of those periods, this is the second in that series, a Victorian Christmas.

As more diverse groups began settling on the North Fork, people gradually began to adopt Christmas traditions from these groups. There was a significant shift from how people celebrated Christmas in colonial times, although the focal point was still on the religious aspect of the holiday. (During this time, American stores were selling plaster and lead nativity figures that were made in Europe, as well as all the materials needed for building and setting up a crèche at home to remind them of the holiday’s true meaning.) All the reasons the Colonial settlers had for not adopting the Christmas traditions of other nationalities and religions seemed to fade.

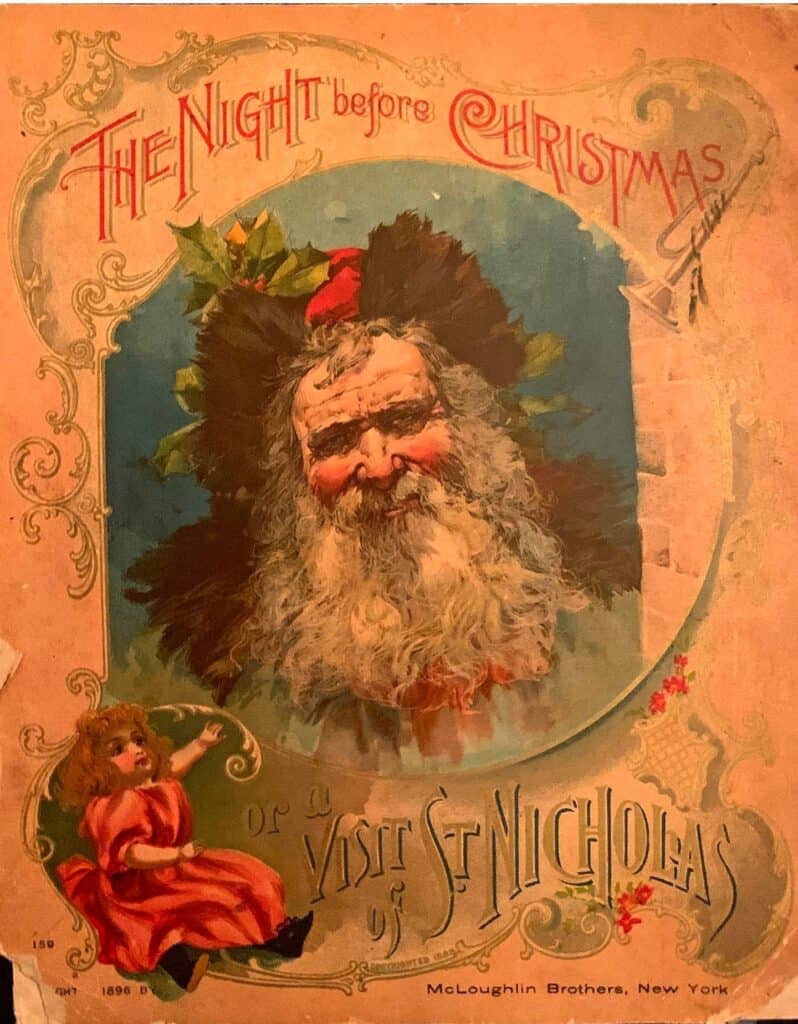

Communication and transportation revolutions made the once somewhat isolated North Fork acutely aware of what was going on in the rest of the country. There was a stronger national media influence on the public in the 19thcentury. Immigration vastly widened the ethnic and religious pluralism that had been a part of American settlement from its beginning. The many Christmases celebrated across the land began to resolve into a more singular and widely celebrated home holiday. A uniquely American version of Santa Claus emerged when he made his first appearance in the 1822 poem “A Visit From St. Nicholas” by Clement Moore. This poem was heavily promoted through many books, such as ones from the Mcloughlin Bros. publishing firm. Thomas Nast created a version of Santa Claus (based on the traditional German figures) that began making appearances in the popular “Harper’s Bazaar” in the early 1860s, and many other publications, such as Godey’s Lady’s Book, all contributed to how Americans perceived Christmas traditions, as did the writings of Charles Dickens (A Christmas Carol), who was hugely popular at the time.

Queen Victoria had a tremendous influence on fashion in this period. When her German-born Prince Consort, Albert, installed an evergreen in the palace as a Christmas tree, the world seemed to follow suit. By the 1850s, Americans had fallen in love with the German custom. In true Victorian fashion, they could not refrain from the urge to make the tree a showpiece for the artistic arrangement of ‘glittering baubles, the stars, angels, etc.’ Trees began to be laden with the extreme ornamentation that often surrounded the parlors in which they sat. Tree decoration soon became big business. As early as 1870, American businessmen began to import large quantities of ornaments from Germany to be sold on street corners and, later, in toy shops and variety stores. Vendors hawked glass ornaments and balls in bright colors, tin cut in all imaginable shapes and wax angels with spun glass wings. In 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant declared Christmas a federal holiday, In 1889, President Benjamin Harrison had the first documented Christmas tree in the White House in the Oval Room. Electricity was not installed in the White House until 1891, so Harrison’s grandchildren decorated the tree with candles. In 1894, President Grover Cleveland had the first electric lights on a family tree in the White House.

The tradition of decorating with greens at Christmas has pagan roots and was very strong in England. Early colonists brought this tradition with them, and although its popularity was suppressed by the Puritans it experienced a strong resurgence in Victorian times. As mentioned, Charles Dickens was an extremely popular author in Victorian England and America. His vivid descriptions of Christmas celebrations and decorations strongly influenced American customs, and his writings created enduring traditions.

The Civil War intensified Christmas’ appeal. Its sentimental celebration of family matched the yearnings of soldiers and those they left behind. Its message of peace and goodwill spoke to the most immediate prayers of all Americans.

The perfection of chromolithography and the improvement of the mailing system created a craze for card sending for all occasions, Christmas being its king season, and the tradition persists. Some of the imagery presented on Christmas cards even influenced public tastes on how to decorate for Christmas.

Christmas gift-giving blossomed in the 1870s and 1880s. Gifts had played a relatively modest role in Christmases of the past. Now they lavishly gilded the already popular holiday. In the 1820s, ’30s, and ’40s, merchants noticed the growing role of gifts in the celebration of Christmas and New Year. Starting in the mid-to-late- 1850s, imaginative importers, craftspersons and storekeepers consciously reshaped the holidays to their own ends even as shoppers elevated the place of Christmas gifts in their home holiday. While families could give handmade presents, people could now purchase mass-produced gifts, such as dolls, stuffed toys like the teddy bear, and wooden toys like trains and cars.

The feast was still at the center of the Victorian Christmas, and the heart of the celebration was a special meat, usually, one that wasn’t eaten during the rest of the year (like quail, pheasant, goose, or turkey, depending on the family.) All manner of delicacies, such as oysters, custards, olive, celery, stuffing, jellies, sherbert, cheese balls, toasted crackers, and plum pudding with hard sauce, was also at the table. Parties were held where toddy, nogs, or wassails were served, usually spiked with liquor and often based on old family recipes.

Many of the Christmas holiday traditions Americans honor in the early 21st century were shaped in the 19th century.