A 20th Century Christmas

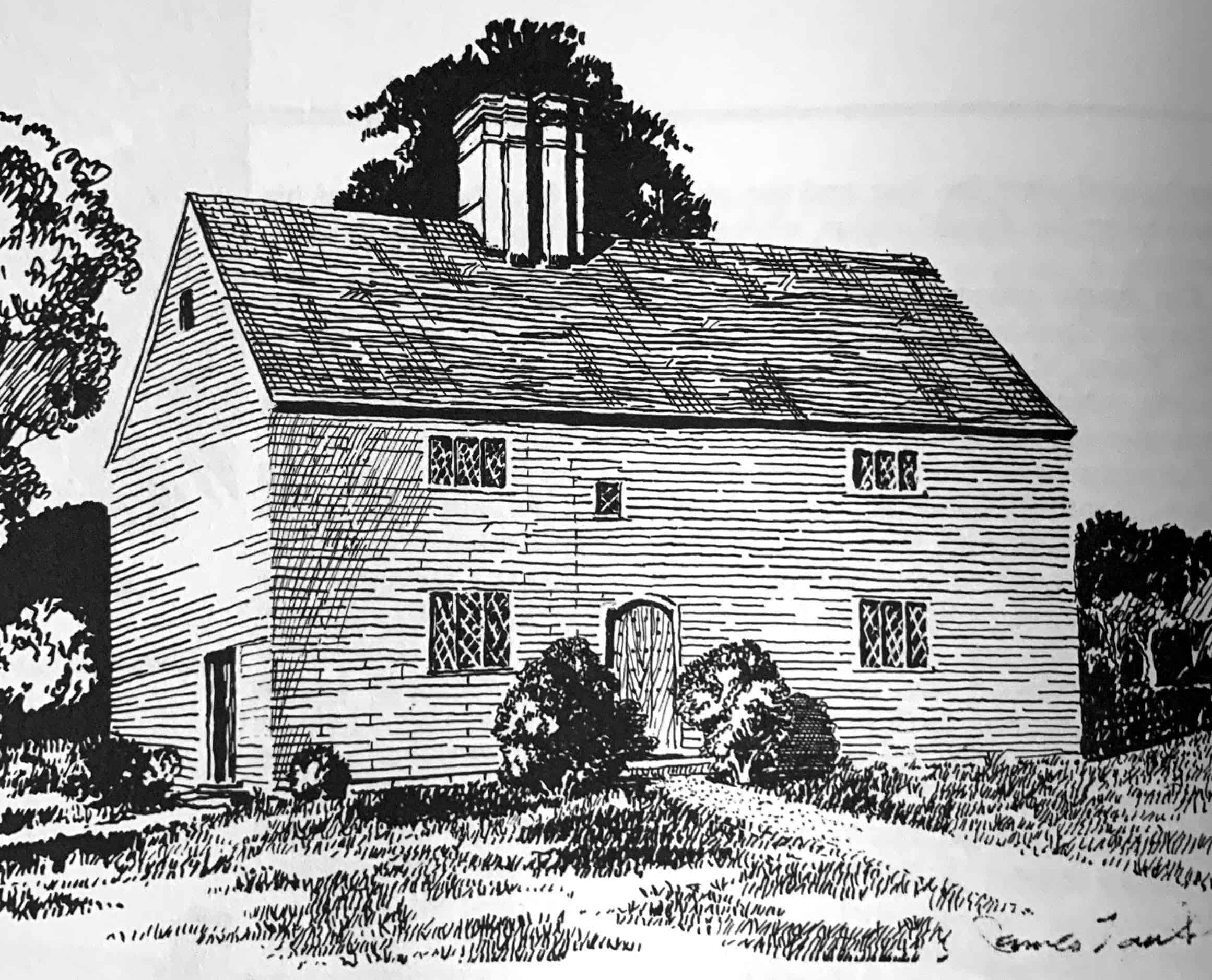

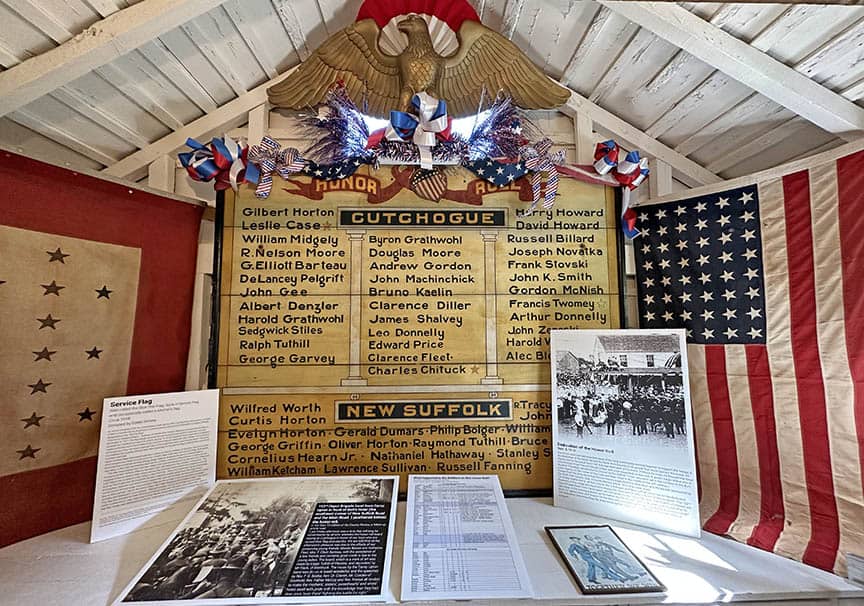

As part of our tree lighting and Holiday event on Dec. 3, we interpreted three of our historic buildings to represent Christmas during that period. The Old House, a colonial Christmas, the Wickham House, a Victorian Christmas, and the Schoolhouse, a mid-century Christmas. This is the final of three consecutive blogs which talk about each one of those periods, this is the third in that series, a 20th Century Christmas.

Christmas in the 20th century reflected the changes from the 19th century. The holiday traditions stayed the same for the most part; people continued to put up Christmas trees, filled stockings, and held holiday parties. The main change came with the commercialization of the holiday. Retail stores had all gotten the message by the early 20th century and began to increase their advertising and gift selection well before Christmas. The toy aspect of Christmas grew even more as the toy market expanded when many classic toys were invented in the early part of the century. For example, the Teddy Bear designed in 1902 by the Michtoms after a popular newspaper political cartoon of Theodore Roosevelt refusing to shoot a bear. They went on to found the Ideal Toy Company, which would create many more popular toys. Even during the Great Depression and the World Wars, people still tried to keep up the traditions as best as possible. During this period, when people did not have much money, they still tried to get gifts for their family, particularly their children, because it was now deeply ingrained in the holiday culture. However, many who grew up during the depression tell stories of receiving nothing but an orange or small trinket as their Christmas present.

Although Thomas Nast created an enduring image of Santa in the national consciousness, in 1931, Coca-Cola created an image of Santa that would embody the character for the rest of the century. Similar Santas existed to the Coca-Cola Santa, but their vast advertising push using the image solidified it as a 20th-century icon.

Christmas saw a boom in post-war America with a larger middle class and more children. More people could afford more things for Christmas. Many parents that grew up during the Great Depression were able to give their children the idealized Christmas that the depression prevented them from having. Parties were still popular, but for many people, Christmas day became a time just for the family. For the most part, Christmas has remained relatively consistent, and despite advances in commercialization, traditions formed in the Victorian Era persist. This post-war boom made the Christmas of the 1950s one of the biggest and gaudiest yet. Wide-spread prosperity meant most were lucky enough to afford Christmas celebrations. Women’s magazines pushed for the ideal Christmas season, full of elaborate recipes and decor.

With the rising popularity of the radio, the 1920s also saw the first Christmas radio broadcast when, in 1922, Arthur Burrow presented “The Truth About Father Christmas.” In the late 1940s, television started becoming popular, and with it came a host of Christmas specials. Stars like Nat King Cole and Bing Crosby recorded Christmas songs, and popular shows like I Love Lucy recorded special Christmas episodes. In the early 60s, children’s television specials were introduced, and many from that period are still beloved and enduring. In 1964, Rudolph the Red Nose Reindeer took advantage of advances in stop-action animation, which had been around since the turn of the century. Using traditional animation, A Charlie Brown Christmas explores the true meaning of Christmas and uses an unorthodox mix of traditional Christmas music and jazz. Many of the jazz pieces endure as popular Christmas music today.

Speaking of Rudolph, his character, everyone’s favorite red-nosed reindeer, was created in 1939 by Montgomery Ward. However, it wasn’t until a decade later that Gene Autry released the song that we all learned as kids.

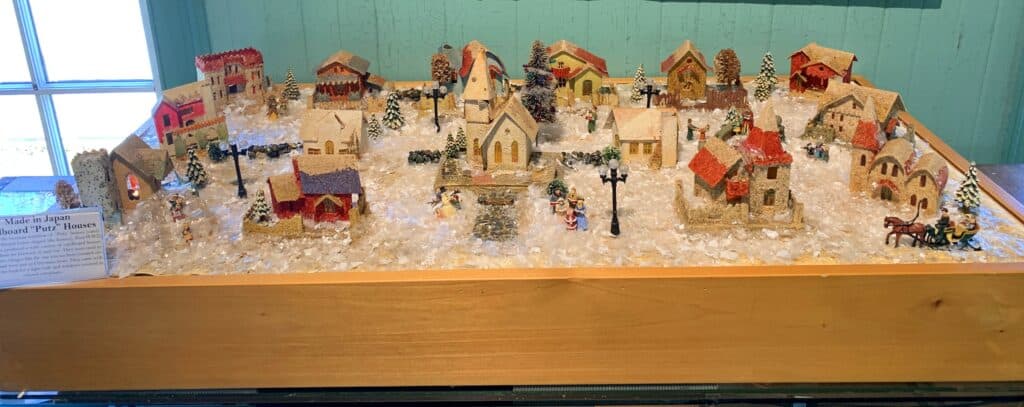

In 1946, the Japanese government put on a big push to rebuild and revitalize war-torn Japan. Inexpensive, cheap, low-end dime-store quality goods began flooding the market. These goods included a variation of the “Putz” cardboard houses with a new feature, a hole in the back to accommodate a C6 lightbulb. They produced other items like the Pixie-elves with plastic faces and felt bodies (ancestor of today’s “elf on the shelf”), Santa’s, ornaments made of felt and cotton batting and glitzy blown silvered glass, and all sorts of cheap Christmas decorations that became very popular. Gurley Novelty produced Gurley candles, which began in Buffalo, New York, in 1939 using recycled paraffin wax; they created holiday novelty candles, particularly Christmas ones, until the early ’70s. These were strictly ornamental and not meant to be burned.

Large plastic illuminated figures were put on suburban lawns, and hot burning C9 Christmas bulbs outlined houses and lit trees.

Most of the Christmas traditions we have mentioned came from other countries, but not the poinsettia. They were brought to the U.S. in 1826 by Joel Roberts Poinsett, the first U.S. minister to Mexico, who also happened to be a botanist from South Carolina. Poinsettias solidified their status as a holiday classic in the United States in the 1950s after a Californian farmer named Eckes cultivated and marketed hardier versions of the tropical plant.

Bubble lights for Christmas decorations were patented in 1944 and became very popular through the 70s when the smaller fairy lights were introduced and adopted.

We hope you’ve enjoyed our Christmas through the ages. Of course, there is so much more to Christmas (not to mention the religious aspect) than we can get into here; we’ve just tried to create an overview that’s brief, informative, and entertaining. Please enjoy the holiday as you continue to make traditions of your own.