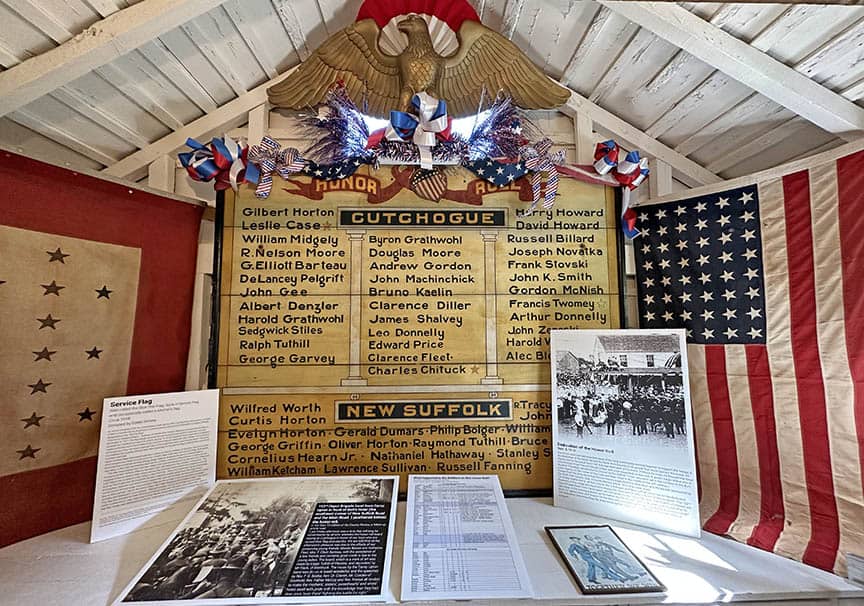

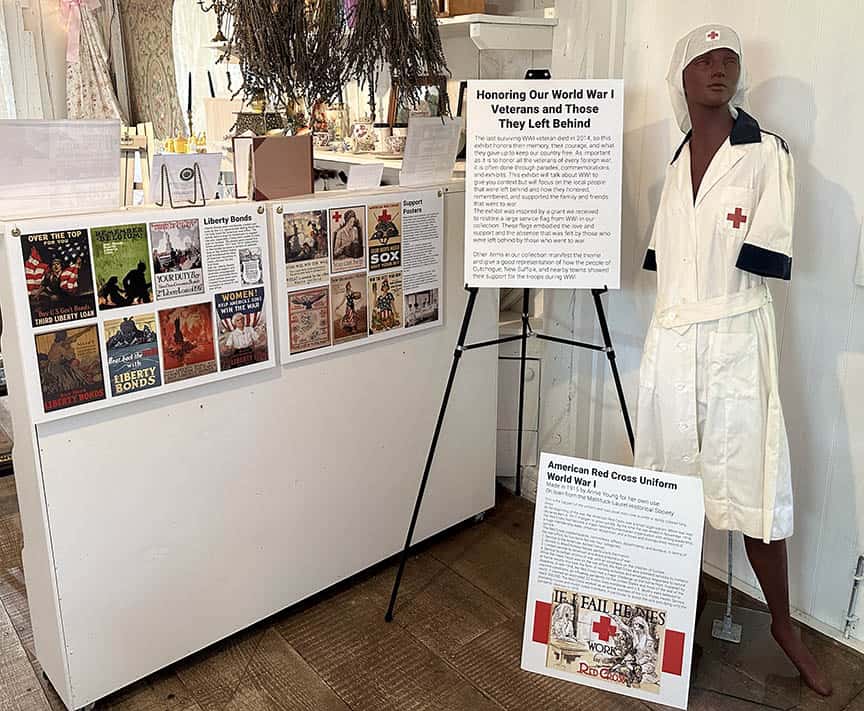

Last year, we presented a temporary exhibit entitled “Honoring our WWI Veterans and those they left behind.” For Memorial Day, we will summarize the exhibit in a Five-part blog series for those unable to see it. It presents a fascinating window into how people of the North Fork, particularly those of the Cutchogue and New Suffolk area, honored and supported their veterans of the First World War. In this Blog, we talk about the roles of the Dough Boy and the Red Cross Nurse.

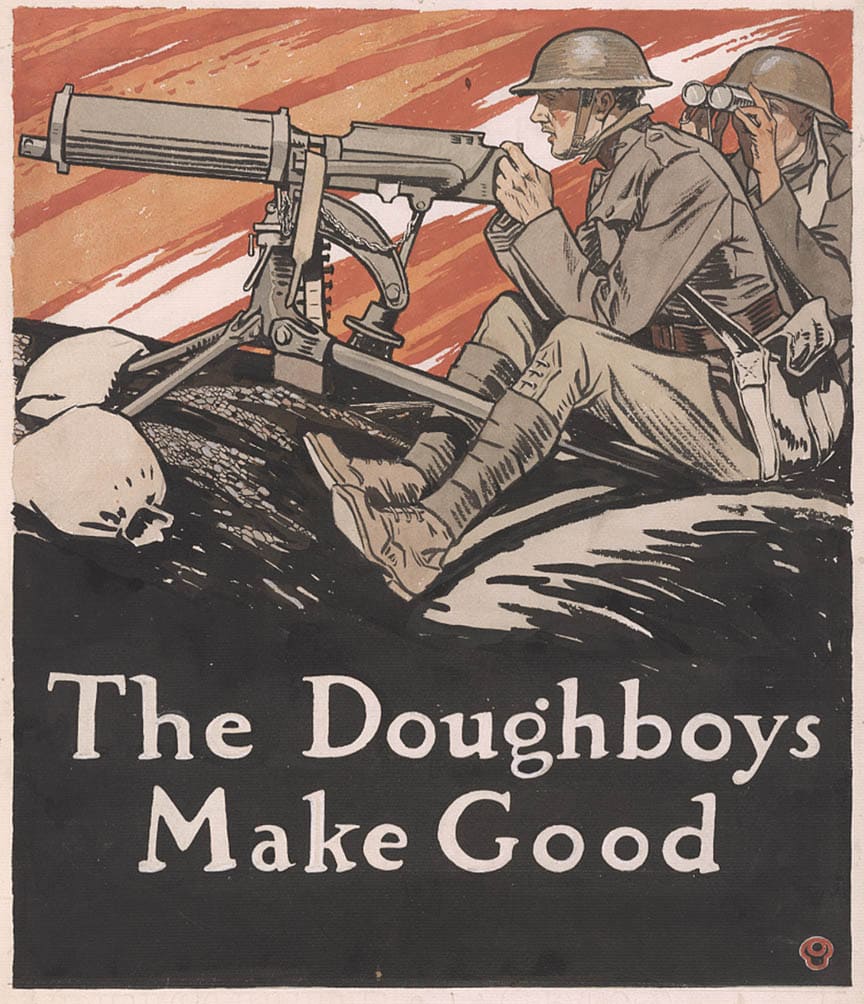

During the WWI Great War, doughboys in France wore heavy wool olive drab uniforms first developed in 1912, such as the one on display here. These wool uniforms were warm, retained body heat even when wet, and were tough and durable. But they were also heavy, extremely hot in the summer, difficult to clean, itchy, and scratchy to wear.

There are many origin stories for “Doughboys,” there is one with strong historical support. Likely, the name attached early to the Americans from U.S. military operations on the Mexican border.

Reconciliation with Mexico had just concluded in 1916 when marching foot soldiers were often seen covered in white adobe dust; the foot soldiers were called “adobes” or “dobies” by mounted troops. These dobies, or Doughboys, were redeployed to Europe within a few months.

A Doughboy’s uniform consisted of socks, long underwear, a pullover shirt, breeches or trousers, and a tunic with a high collar at the neck. This tunic was called the M1917 or model 1917 for the year it was issued. Also present on this uniform were wool spiral wrap puttees. Puttees, an East Indian term, were made of wool and tightly wrapped around the legs from the ankles to the knees. Worn outside the soldier’s pants, puttees were initially believed to increase muscle stamina, but their best contribution was an extra layer of protection against mud. On the head of the manikin is the 1917 steel helmet used by the doughboys. This would have been worn in the trenches, on the front line, under fire, or in combat and became their icon symbol. Also shown is an aluminum canteen with a khaki cover. The ammunition container is for theM1 Garand rifle, which fires the Cartridge, Ball, Caliber .30 M2, known to civilians as the .30-06 Springfield cartridge.

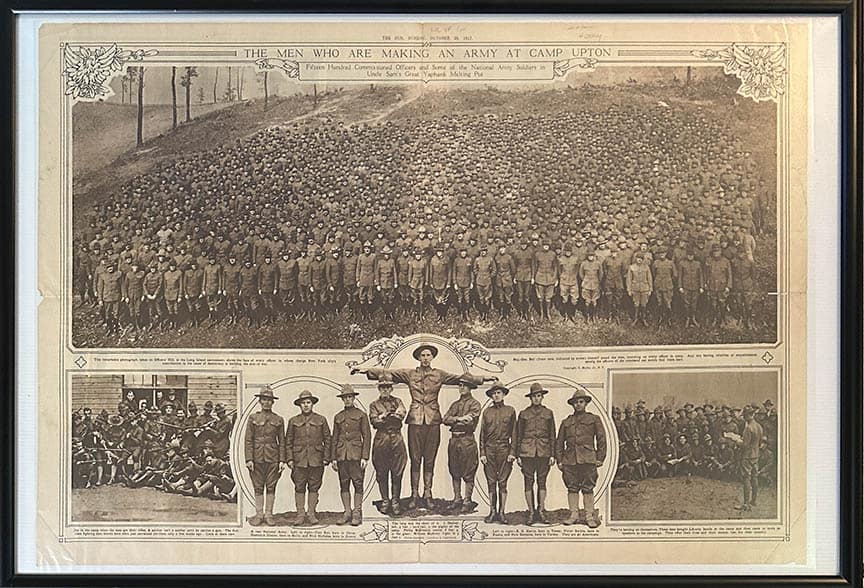

Locally, the Doughboys were initially deployed to Camp Upton, created in 1917, and located in Yaphank, on the site of the current Brookhaven Laboratory. Camp Upton was the point of embarkation of the United States Army during WWII. (In WWII, it was used to intern enemy aliens.) It had the capacity for 18,000 troops. When scheduled for embarkation aboard troop ships, the units traveled by trains on the Long Island Rail Road to board ferryboats for the overseas piers in Brooklyn or Hoboken.

According to oral history, local residents as far east as Greenport would host one or two soldiers a week on their weekend passes for dinner during WWI and WWII, allowing them to experience a good home-cooked meal. During WWI, North Fork towns increased their budgets to improve local roads, although not so much for soldiers getting home-cooked meals as for soldiers spending their money locally.

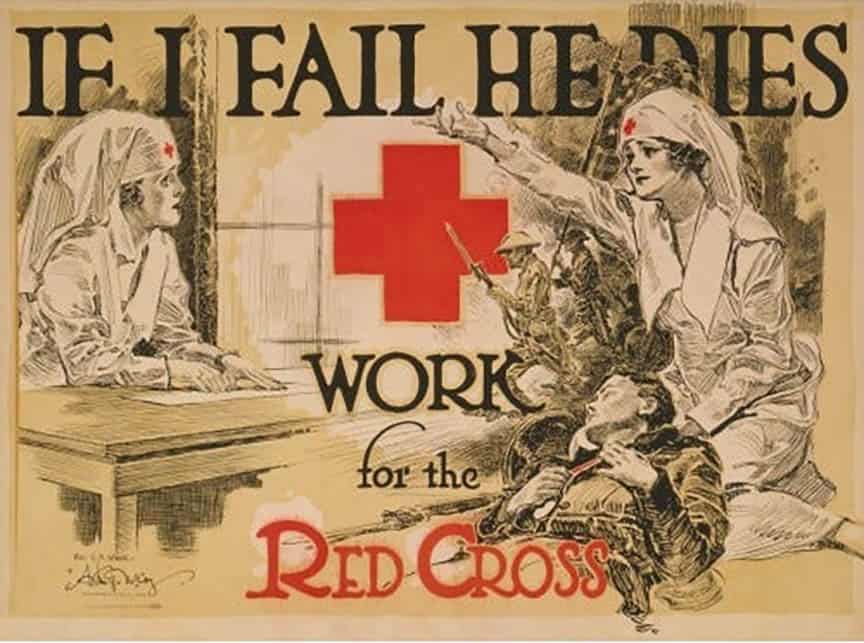

The American Red Cross was a small organization at the beginning of the war. When war was declared on April 6, 1917, it increased. By the time the war ended in November 1918, the Red Cross had become a major national humanitarian organization with solid leadership, a huge membership base, universal recognition, and a broad and distinguished service record.

The Red Cross created boards, committees, offices, departments, and bureaus. In terms of the war effort, its functions fell into four categories.

1. Service to the American Armed Forces.

2. Service to Allied military forces, particularly the French.

3. Limited service to American and Allied prisoners of war.

4. Service to civilian victims of war, with an emphasis on the children of Europe.

While the primary focus was the war effort, the Red Cross also provided services to civilians at home. Mostly, this took the form of nursing activities and emergency responses to natural disasters. In late 1918, the Red Cross met a significant challenge on the home front. Fostered by wartime conditions, an influenza pandemic hit the United States and most of the world. It claimed an estimated 22 million lives worldwide, and U.S. deaths were believed to reach 500,000. The Red Cross worked as an active auxiliary of the U.S. Public Health Service, providing nurses and motor corps members, in particular, to assist the sick and dying until the pandemic died out in 1919.

Up next: Part III, Honoring our WWI Veterans and those they left behind: Women’s role in WWI.