At this time of year, our thoughts seem to turn towards the macabre, and witchcraft may be on our minds. Salem, Massachusetts, is the area we all know of that had its trouble with witches, but how many of us know that witches were of great concern here on the Eastern End of Long Island as well?

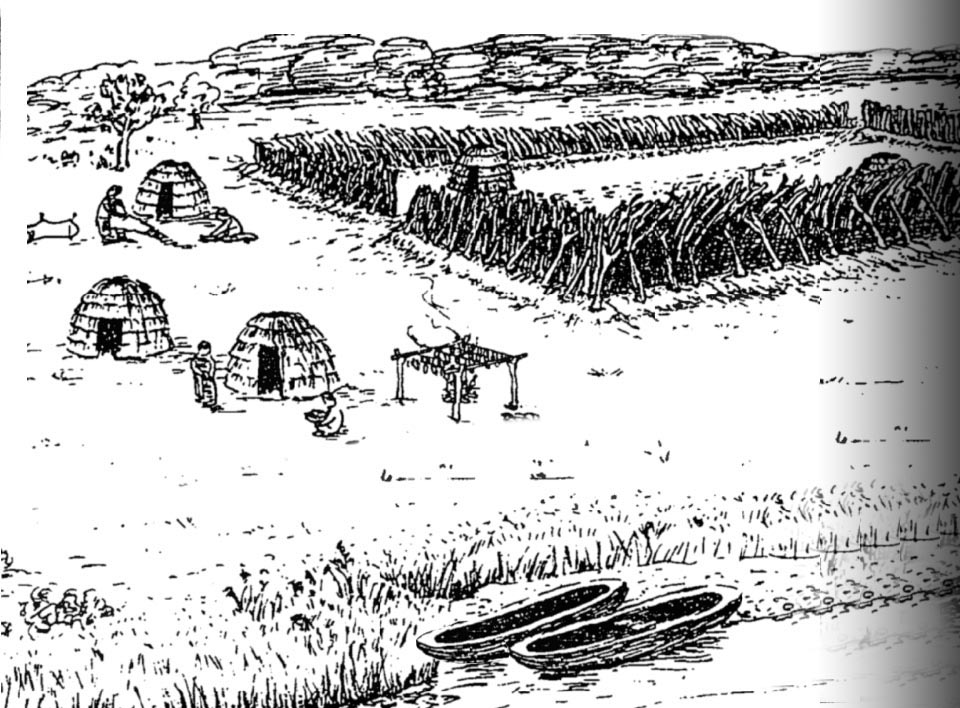

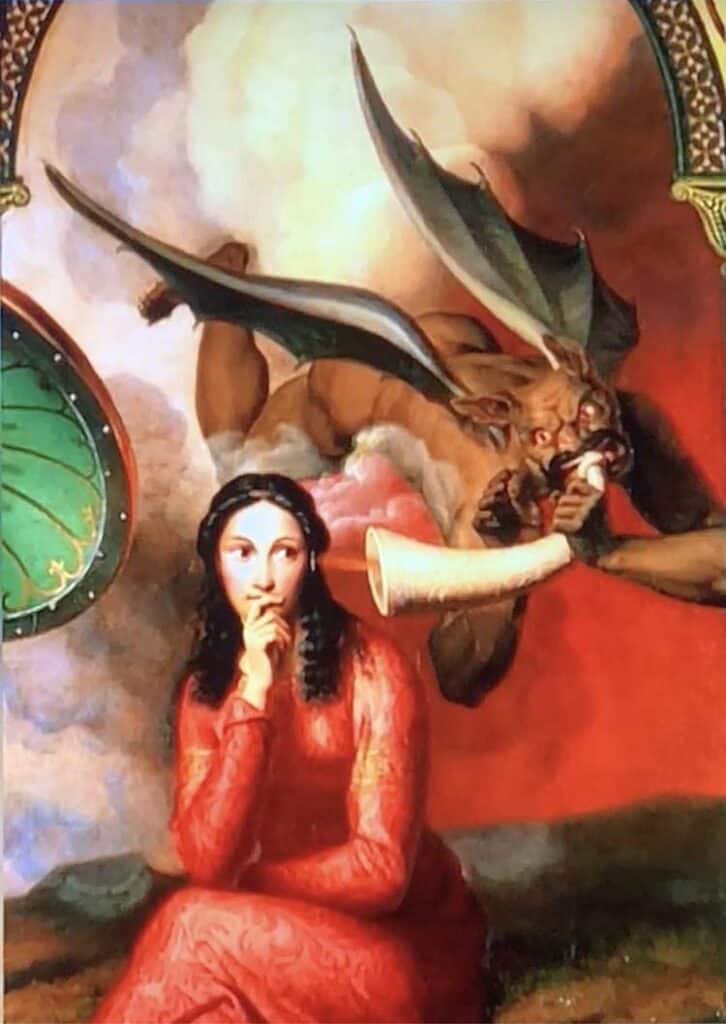

We often forget just how dark the past was. Lighting was primitive with small candles or burning reeds illuminating only the task at hand, while the rest of the room and house remained dim. Darkness exacerbated an already unnerving aspect of life at this time- people believed in black magic and demons. The earliest colonists that settled here in the 17th century were deeply religious. Protestant preachers, trying to bring their flock closer to God, often over-emphasized the devil’s role in their lives, sometimes making his metaphorical characterizations seem too real in their sermons. Many believed Satan was always on the prowl, and those who did not have the moral strength to resist his temptations could owe a debt to the devil, and as a result, they did his bidding. They believed there were interlocutors between the devil and the colonists, and those interlocutors were witches.

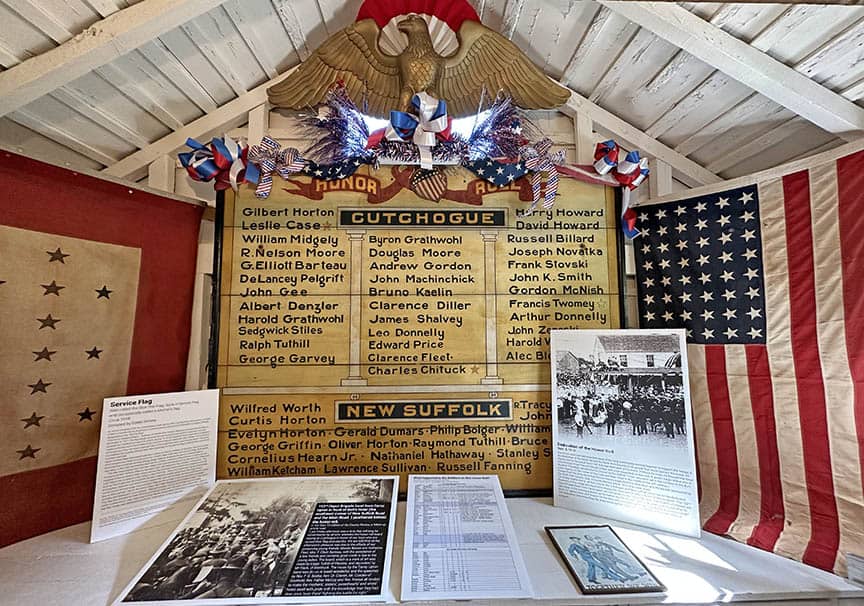

Evidence found in the Old House in Cutchogue indicates that there was a real fear of these witches, and residents of the house felt they needed to take steps to protect themselves against them.

Tear-dropped shaped burn marks found on the fireplace hearth lintel of the Old House is one of the more common apotropaic (having the power to avert evil influences or bad luck) symbols found in post-medieval vernacular architecture. It was believed that these burn marks, created by candle flame or hot poker, prevented witches and other evil spirits/beings from entering the house, creating barriers they could not cross. (The chimney was thought to be a common entry point.)

Within the past 25 years, a great deal of study has been devoted to apotropaic marks in general, and scholars had come to the conclusion that these types of burn marks found in many colonial homes and those that come before them were not incidental, but used to ward off witches.

Similarly, the power to repel witches was assigned to the poppets, which were found in the floor of the Old House next to the kitchen door during the 1940 restoration work. These poppets are more commonly found in houses in Europe and are rarely found in America, making the Old House poppets historically significant and of great interest to scholars.

In East Hampton, in 1658, a middle-aged woman named Elizabeth (Goody) Garlick was accused of witchcraft. Neighbors claimed she was casting spells on them and their families and farm animals. The charges were serious; at the time, witchcraft was a capital crime, and she could have lost her life. In particular, she had turned a “hateful gaze” towards a young woman named Elizabeth Gardiner Howell, the daughter of Lion Gardiner. Howell had just given birth. After the birth, she became ill and believed she had become bewitched. She claimed to have seen the dark figure of a witch in the darkness at the end of her bed. She swore the witch was Goody Garlick. Shortly after that, Elizabeth Gardiner Howell was dead. Garlick was accused of her death through witchcraft, and by the time the trial began, 13 witnesses had come forward, citing additional evidence of witchery. The local justices feared they did not know enough about demonology to reach an accurate verdict and did not want to condemn an innocent woman, nor did they want to set a witch free, so they referred the case to a higher court, which was in Connecticut, the body that governed the east end of Long Island during early colonial times.

Connecticut’s new governor, John Winthrop, Jr., presided over the trial. Winthrop did not find Goody Garlick innocent. However, he also could not find her guilty, so although she was not fully acquitted, they refused to find her guilty. He ordered the community to put aside any grievances they might have with her and allow her to live out her life peacefully. At this time in history, science was getting a firmer foothold in society, and Winthrop’s judgments often represented the foothold science had over religion.

So while there is no historical evidence that witches existed during the colonial period, more and more evidence is coming to light that our forefathers living here on the East End, feared them and took measures to protect themselves and their families against them.