Historic places are a tangible reminder of our shared heritage. They provide a connection to the past, allowing us to reflect on who we were and how much we’ve grown. Historic preservation is not merely about celebrating our connection to the past but also about understanding the impact of such efforts.

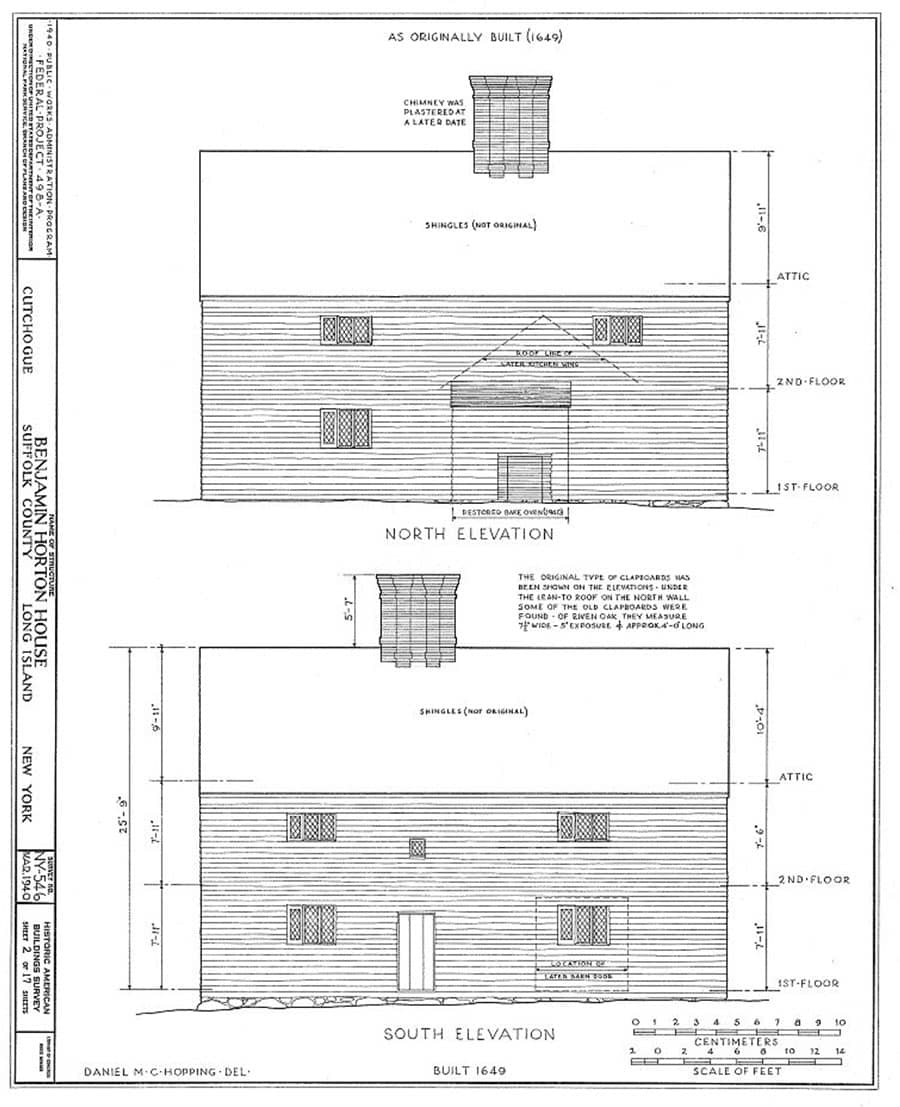

In the United States, the roots of historic preservation can be traced back to sites such as Washington’s Headquarters State historic site in Newburgh, New York. Recognized in 1850, it has the honor of being the first-ever property designated and operated as a historic site by a U.S. state. Shortly after, in 1858, the preservation of George Washington’s Mount Vernon was accomplished. By the late 19th century, organizations dedicated to the cause emerged. Preservation Virginia, founded in 1889, took the lead as the nation’s first statewide historic preservation group. The 20th century saw a flurry of preservation activities, with influential figures like Charles E. Peterson playing a pivotal role. He was instrumental in founding the Historic American Buildings Survey, also known as HABS, which traveled around the United States, taking photos and creating architectural drawings of architecturally significant buildings to document America’s built legacy. His work directly influenced the formation of the first graduate degree program in historic preservations at Columbia University. It was

a HABS architect traveling through Cutchogue in 1938 who was a crucial figure in recognizing and highlighting the need for the conservation and restoration of the Old House in Cutchouge. In East Hampton, HABS architects meticulously diagramed the house and workshops of the Dominy Family, a three-generation dynasty responsible for building most of the furniture on the East End of Long Island from the mid-1600s to the mid-1800s. Charles F. Hummel recreated the Winterthur Museum workshops using these diagrams to house an important collection of Dominy tools. The Dominy house, which connected the workshops, was demolished in the mid-1940s. Still, the East Hampton Historical Society restored it to its original position in town, using the HABS diagrams and pictures.

The first Historic District Zoning ordinance in the U.S. was established in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1931; the inception of the US National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1949 created a non-profit with the vision of revitalizing communities by preserving their historical essence.

To truly understand the all-encompassing importance of historic preservation, one must return to the 1963 tragic demolition of New York City’s Pennsylvania Station. This was a turning point, pushing sentiment strongly in favor of preservation. The loss of a building that millions of people had connected to, shared memories in, where thousands of people had proposed or had their first kiss, sent their sons off to war, sent their children off to college, or welcomed their grandchildren visiting for the first time, Penn Station wasn’t just an architectural wonder, beneath its elaborate façade, its structure held a tangible connection to memories of millions of people. That same year saw the establishment of numerous academic programs centered on historic preservation.

There are real-world examples of historic preservation tying us to our shared cultural identity. Preserved sites anchor communities, representing collective memories, values, and experiences that shape our cultural identity. For example, the Statue of Liberty was the gateway for over 12 million immigrants to the United States.

Ellis Island holds the collective memories of countless families beginning their American dream. Preserving this site ensures that stories of hope, determination, and pursuit of a better life remain accessible to all, reminding the nation of its diverse roots.

The Alamo is much more than just an old mission building. It encapsulates the values of resistance, freedom, and determination. The narratives of those who stood their ground there resonate with core American values, making its preservation essential for all Americans to understand and honor a collective past.

The world watched in collective sorrow when a fire ravaged the Notre Dame Cathedral in France in 2019. This wasn’t just a structure burning; it was centuries of history, art, devotion, spirituality, sanctity, and shared human experiences at risk. The global outpouring of support and the commitment to restore it highlights the intrinsic value of anchoring communities and preserving cultural identity.

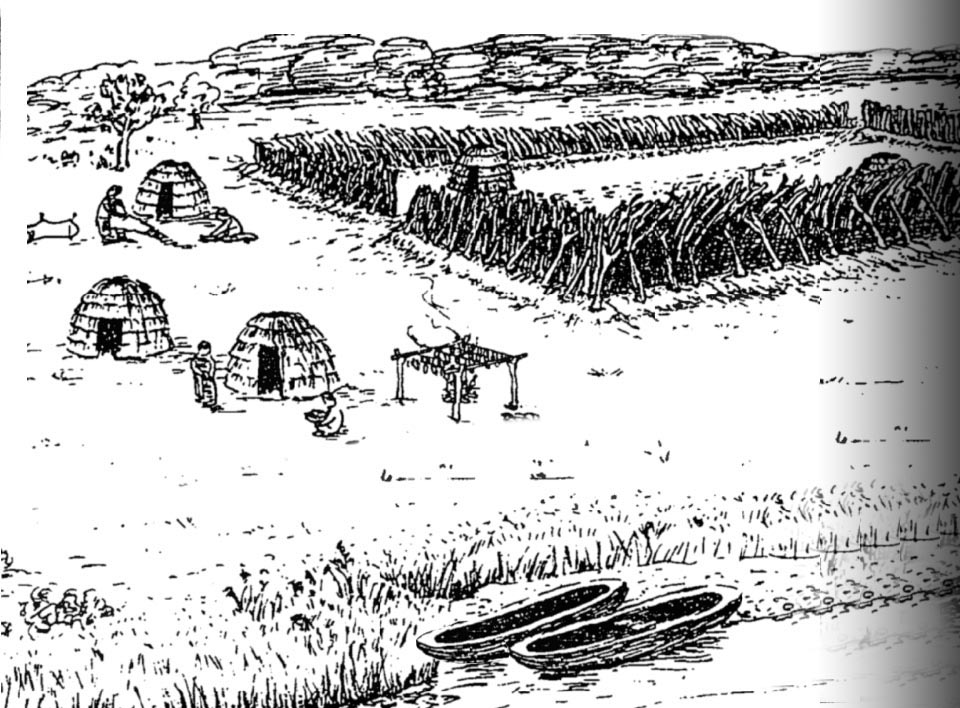

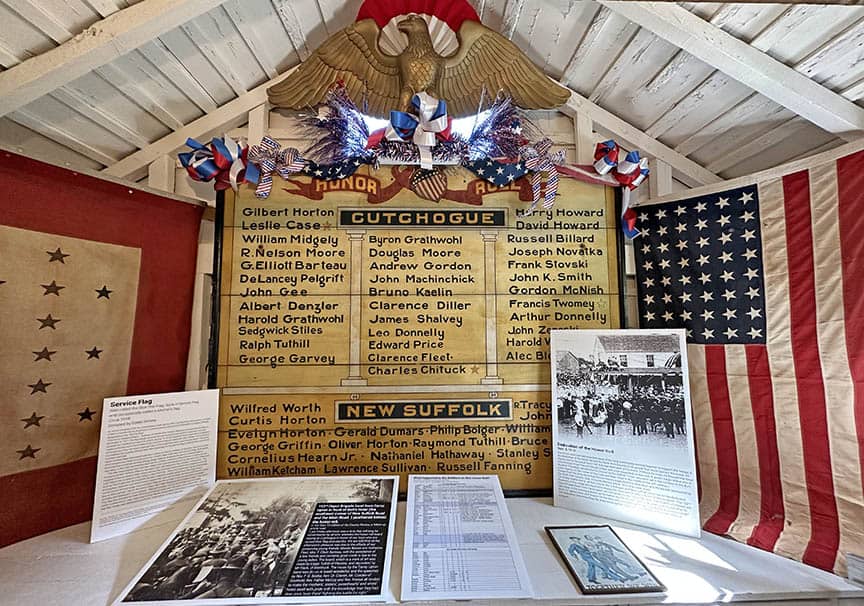

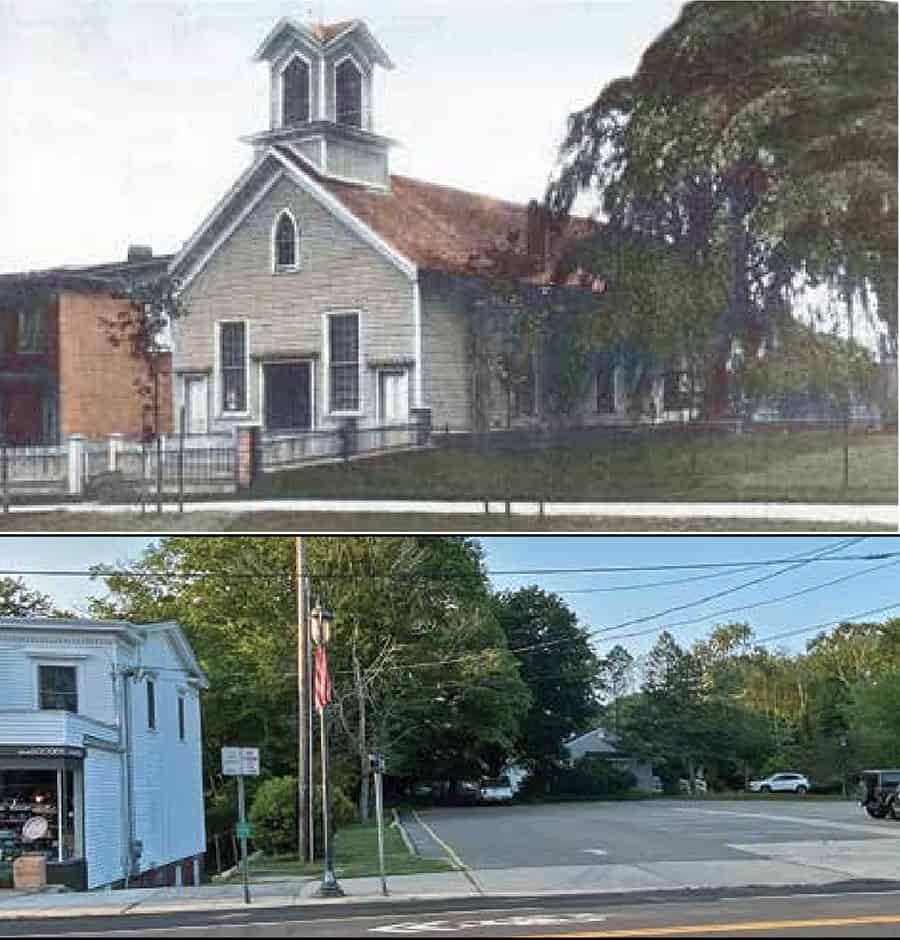

Locally, almost every town on the East End has some historical society that was instrumental in preserving significant historic buildings. The sites they maintain are visual representations of the early founding of our towns and even our nation. Community members fought diligently for almost 30 years and successfully managed to preserve the land where Fort Corchaug is. This site is considered one of the nation’s most significant sites of first Colonial contact. Without the valiant efforts of those community members, it would have been bulldozed for development. It is now available for future archeological exploration that will continue to inform us and increase our understanding of a period of which we know very little.

On the Village Green, the Wickham House, the Schoolhouse, the Red Barn, and the Carriage House were all moved to prevent their imminent demolition. These buildings collectively tell the story of the founding of Cutchogue and have hosted thousands of visitors a year who want to hear these stories and learn about our history.

It’s also been shown that historic districts in local towns can boost local economies. They create jobs and result in higher property values. As we know, on the East End, small towns with historic districts often become travel destinations in their own right. In historic districts, local artisans, artists, and craftsmen find a market for their products, promoting traditional and indigenous art forms and continuing the legacy of old-world construction techniques that seemingly have no place in new developments.

Preservation is also environmentally and budget-friendly. By reusing existing buildings, we conserve resources and reduce the need for new construction materials. Instead of demolishing and building anew, which requires significant resources and energy, adapting existing structures is eco-friendly and budget-friendly. In small towns such as ours, you can find houses with hand-crafted artisan details, something unique that can not be duplicated or, if so, would cost a fortune today.

If you still wonder why preservation is important, imagine wide highways and acres of track housing that all look the same. Homes that are viewed as disposable and replaceable, A world where identical ticky-tacky houses replace all the houses with a past, exciting stories, and folklore with no history attached to them.

Historic places foster community pride and connection. When you stand in a place where history has happened, you don’t just learn about the past; you feel it and live it. You can be a part of history by helping to preserve it, from advocating for the preservation of a local historic site to volunteering in restoration projects at local historical societies. And if this is too much for you now, visit a historic community or a historical society and appreciate the old world charm and understand firsthand why it is worthy of preservation.

Our history defines us. By preserving it, we leave a legacy for future generations, a charming place where we can connect with our ancestors and share timeless moments with our loved ones, a place where we can learn from, cherish, and be inspired by the tales of our shared journey through life and time. The past is the foundation for our future.