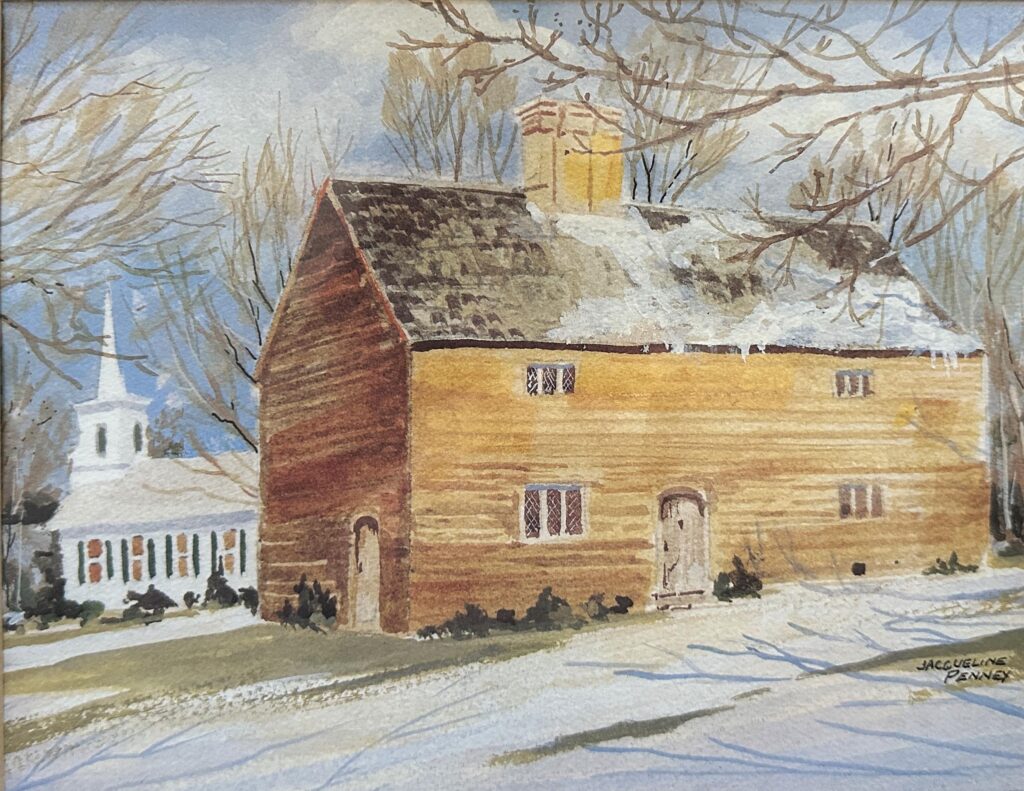

Historical figures, ancient or recent, leave footprints of their time here, and they are all around us. Sometimes, it’s the buildings they built, the monuments they erected, or the towns they founded. In Jacqueline (Jackie) Penney’s case, it was the paintings she painted. These footprints may go unnoticed, but they are all around us; all we have to do is be aware and look out for them. They are right behind you as you check out a book in the Cutchogue-New Suffolk Free Library, hanging in the halls of the Eastern Long Island Hospital, in the restaurants and public buildings we frequent, and maybe even hanging in your own home.

Jackie had a talent for capturing everything about the North Fork that makes it the North Fork—everything she loved about it. That love came through in her paintings, making them special to everyone who viewed and owned them.

Her website, which is still up, states, “She captures the essence of the landscape; the movement found in a seascape; and in all her work a thoughtful, peaceful mood. Her paintings invite one to pause and rest and provide a simple yet elegant expression of the ordinary transformed.”

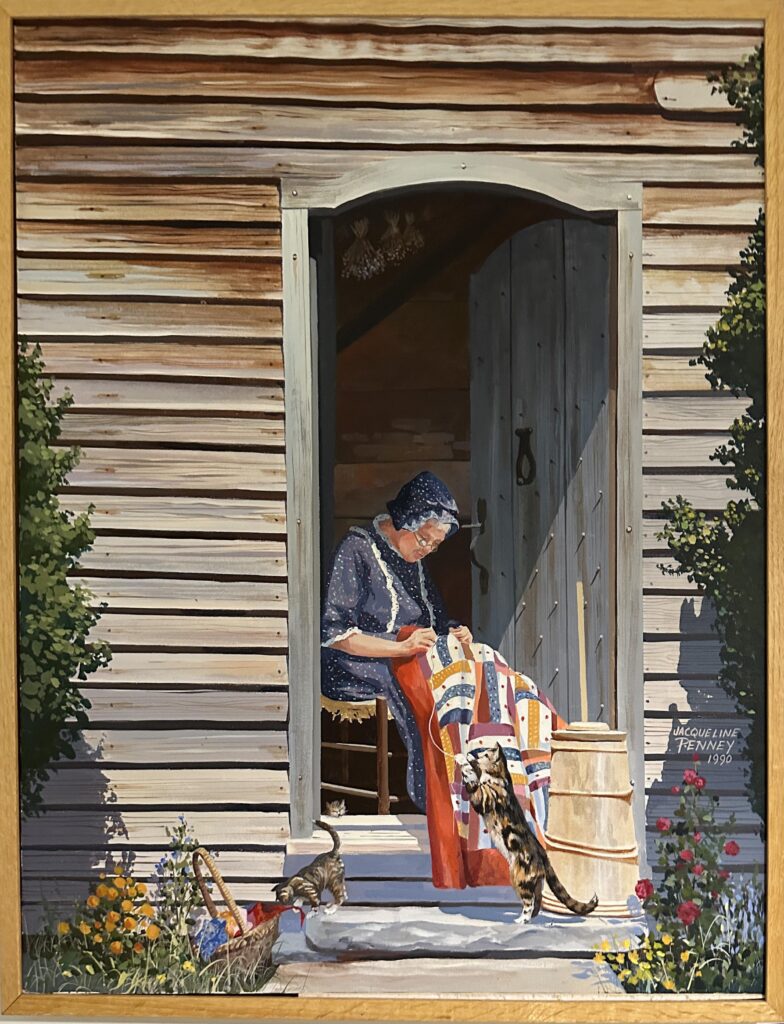

But Jackie wasn’t just a passive chronicler of the imagery of the area; she got involved in the community as well. She supported the Cutchogue New Suffolk Historical Society and Southold Town. Her painting of Winnifred Billard (a long-time volunteer and North Fork icon in her own right) dressed in colonial garb, sewing a quilt in the frame of the front door of the Old House was used for the poster of Southold Town’s 350th-anniversary celebration in 1990. Prints were made of the image, framed and put on note cards, and sold in the Carriage House to help raise money for the council. The original is framed and hanging in the Local History Room in the Cutchogue Library.

She painted many other views of the Village Green, and hundreds of prints were sold to support the council. Many are still available in the Carriage House today.

She wrote five books, including a memoir in 2012 entitled “Me Painting Me, A Memoir.” She won many major awards and was exhibited all over the world. But the memory of her that lives on locally is from the imagery she captured in her paintings that are still on display. She also lives on in her impact on the students she taught. Last year, in 2023, the Cutchogue Library put on a show called “Influences,” which posed the question to viewers: can you see a teacher’s influence in their students’ work? Jackie was briefly a teacher of Diane Alec Smith, who is also a teacher and her students’ work were on display too. The paintings were mixed to see if the viewer could figure out who painted what to convey the extent of a teacher’s influence.

In 1999, Jackie won a National Competition sponsored by Watercolor Magazine and was invited with other awarded artists to a week at the Forbes Trinchera Ranch in Costilla County, Colo. Her work is on display in nine permanent collections and in the homes of thousands who have purchased her work over these many years.

Jackie lived for years in her distinctive Cutchogue studio — a renovated 1840s red barn on North Street. She instructed hundreds of art students. She had a passion for teaching and was particularly gifted in inspiring others to develop their own creative capacity to “see.”

She lived to be 90 years old, and during her life, she won a scholarship to the Phoenix School of Design in New York City and also attended the Black Mountain College in North Carolina and The Institute of Design in Chicago. Her obituary in the Suffolk Times states that her life was more than her amazing body of artwork and awards and publications. She had a light and mischievous spirit, which was contagious, and anyone who met her knew they would never quite “see” the same, nor be the same after their encounter.