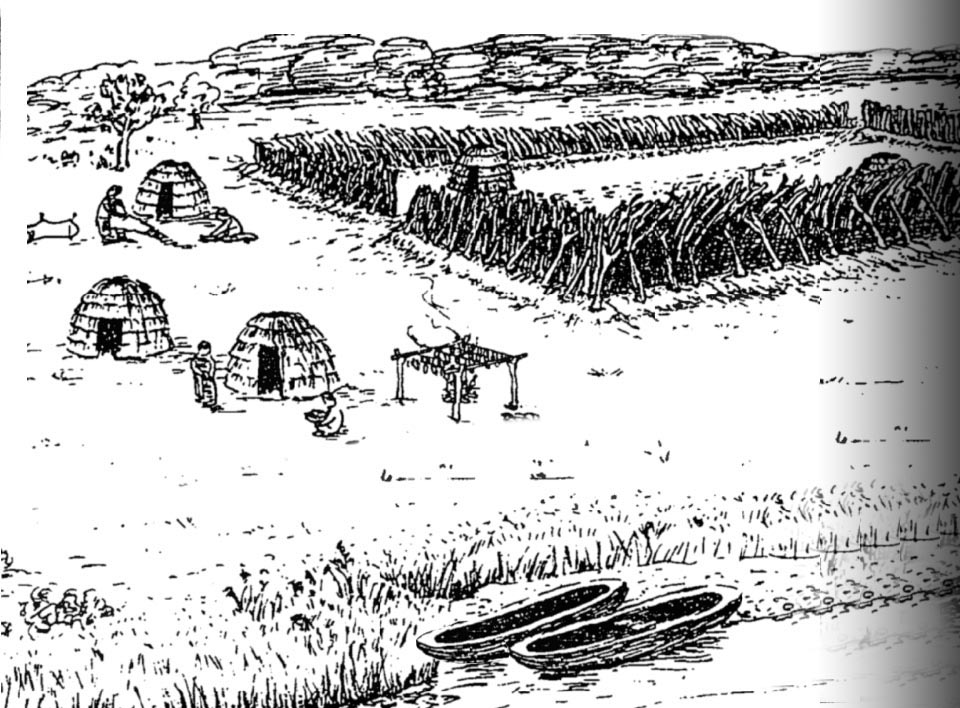

Based on archeological evidence, it is generally agreed upon that Indians inhabited the North Fork of Long Island as long as 10,000 years ago. Spearheads have been found in the area belonging to the Paleo Indians, nomadic hunters. They were hunting wooly mammoths, caribou, and prehistoric bison. Then came the Archaic Indians, who vanished around 1,000 years ago and were succeeded by the Woodland Indians. This group included the Corchaugs, an Algonquin-speaking indigenous group who lived in the Cutchogue and all around the North Fork, when the English settlers arrived on Founder’s Landing in Southold. The Corchaugs were one of 4 tribes on the East End of Long Island when the colonists arrived. The other three tribes included the Montauks in Montauk, the Shinnecocks in Southampton, and the Manhansets on Shelter Island. Four Chiefs who have been believed to be part of the same family (This is up for dispute as it is now thought the word they used for brother may have a friendly, non-familial meaning) ruled the tribes and communicated by smoke signals. 1

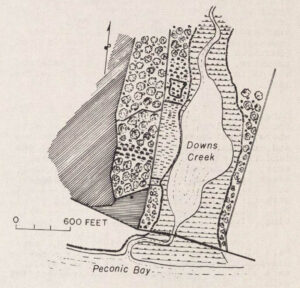

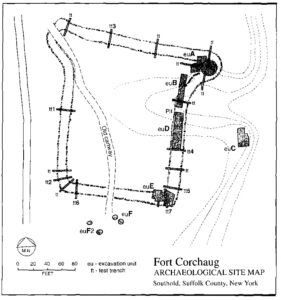

Located less than a mile west of the Village Green in Cutchogue is the Down’s Farm Preserve, the site of “Fort Corchaug” —a palisade fortification built by the Corchaug tribe in the 1630s and abandoned in the 1660s. The Fort may have been to protect the Corchaug tribe from other Indians, built with the help of Europeans. Archaeologist Ralph Solecki, who grew up near the site, described Fort Corchaug in 1992 as the best preserved historic Indian site on the eastern seaboard. At the time, the site had never been cultivated or disturbed in its 340-year old history. He believed it was the last historical remnant of the Corchaug Indians on eastern Long Island and the best preserved of the forts linking the confederacy of the north and south fork Indians, as well as a significant point of first European contact. He began excavating the site in 1946 and continued his interest into the late 20th century. He found the site to contain the most intact and best documented known archaeological deposits preserving evidence of historically documented Indian life in Montauk Country. All other known aboriginal archaeological sites in eastern Long Island, either pre-date or post-date the Historic Contact period, contain fragmentary Historic Contact components or (in most cases) have been destroyed by erosion, development, or looting. Solecki’s diggings culminated in a master’s thesis that the Cutchogue-New Suffolk Historical Council used to get the area named a national historic landmark. 2

The Corchaug Indians lived in the midst of what was the single most important wampum-producing region in seventeenth-century America. Discoveries of substantial amounts of whelk, other shell fragments, sandstone abrading stones, and finished white cylindrical wampum beads in and beyond the embankment walls further suggest that the Corchaug people used the locale as a place for manufacturing wampum shell beads.

The Corchaugs inhabited Long Island’s North Fork from Wading River to Orient Point. Prominent Long Island antiquarian William Wallace Tooker suggested that the name Corchaug derived from the Algonquian word kehchauke, greatest or principal place.” 4 It is not known what this “principal place” referred to—it could have been the Fort on Downs Farm Preserve. John Strong, a prominent native American historian, explains that group identification may not have been important to tribes. When the English came, they took it upon themselves to fix “tribal” boundaries, assign “tribal” names, and designate leaders to make written property purchases. “Gradually,” wrote Strong, “convenient place-name references became accepted as official tribal names both by native groups and by the white settlers.” So, even though the Fort was built in the 1630s, it is possible that it was called “kehchauke” (principal place) and that this name became “Corchaug” because it was important for the new settlers to assign names to places.

Corchaug lands were first colonized by Europeans shortly after the New Haven colony granted a charter to colonists interested in establishing a town of their own in the heart of Corchaug territory in 1649. Naming their new town Southold, they initially settled along its easternmost portions. Intent on expanding their settlements, Southold townspeople only began moving farther west to Cutchogue in 1660 after population losses caused by epidemics and Narragansett raids rendered the Corchaugs unable to resist intrusion onto their lands. Solecki conjects that by 1664 the fort had disappeared, and the Corchaugs were living on a reservation on South Harbor. They disliked the neck and chose to move en mass to Indian Neck but never got the Town to formalize the situation. Eventually they lost ownership of even that land by 1745. It is thought that between 1730 and 1745, the tribe was gone, their land entirely in the hands of new settlers who were arriving in greater numbers and looking for more land to farm. 5

In 1660, the village of Cutchogue was established, a half-mile from the Fort on Downs Farm Preserve. Ironically, the Corchaugs gave “Cutchogue” its name, but the village’s foundation meant their end through displacement and exile. A census taken in 1698 recorded that 40 Indian people, “young and old,” lived within the town of Southold. 6

Fort Corchaug was considered a sporadically occupied place of refuge or a seasonally utilized special-purpose activity area. It proved to be a palisaded strong point and yielded large quantities of Native-made materials, European trade goods, and food remains. Solecki noted that there was evidence of “processes of acculturation,” 7

Cultural resources preserved within the Fort Corchaug Archaeological Site comprise the only known assemblage of deposits archaeologically documenting social, political, and economic relations between Corchaug Indian people and colonists on eastern Long Island during the first half of the 1600s. Information recovered from Fort Corchaug deposits has served as the basis for two extensively-cited graduate theses and most major regional archaeological syntheses published over the past 50 years. 8

Today, the Fort Corchaug Site survives as one of the best preserved archaeological locales associated with seventeenth-century Indian life in the North Atlantic region. Built, occupied, and abandoned at a time when overwhelming demographic, social, and political changes were forcing Corchaug Indian people to sell their lands at Cutchogue and move elsewhere, Fort Corchaug has yielded and continues to possess the potential to yield information of major scientific significance.

Discoveries of substantial numbers of other artifacts confirm that Fort Corchaug contains the most extensive surviving assemblage of archaeological materials documenting trade relationships between Indians and Europeans in Montauk Country during the early seventeenth century.

On February 20, 1985, Solecki did a surface condition assessment of the site with members of the Cutchogue-New Suffolk Historical Society. Visiting the site with Myra Case of the Cutchogue-NewSuffolk Historical Council, Southold Town Supervisor Jean W. Cochran, and several local preservationists on July 2, 1997, Solecki re-identified the open depression at the northeastern corner of the embankment as the locale of the bastion and midden he first excavated nearly sixty years earlier as part of an effort to preserve the area. 9

In a unique collaboration orchestrated by the Peconic Land Trust involving private individuals including the Baxter family and Russell McCall, the Cutchogue-New Suffolk Historical Council, Southold Town, Suffolk County, and New York State, this important Native American fort site, 105 acres of productive farmland, scenic woodland and wetland is conserved in perpetuity. These are areas of great historical and ecological significance, including the 51-acre Downs Farm Preserve. The Town of Southold operates a Nature Center there and maintains the trails at the preserve. For more information, visit the Town’s website. The trails are open daily from dawn until dusk. 10

The Fort Corchaug Archaeological Site was designated as a National Historic Landmark (NHL) on January 20, 1999.

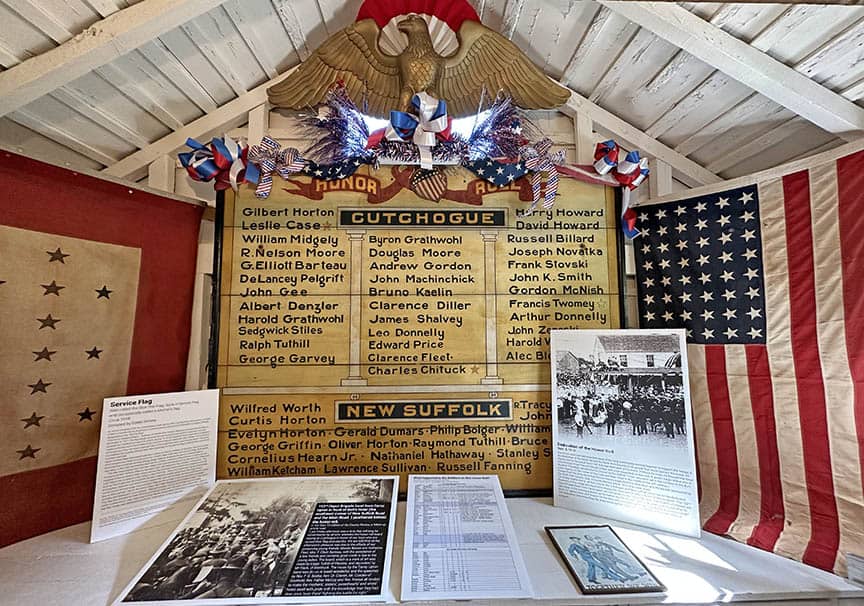

As part of an acknowledgment and commemoration to the local indigenous people, the CNSHC has on permanent display Indian artifacts, such as paint pots, arrowheads, tomahawk heads, and spearheads that were found by local farmers tilling their land.

1. Wacker, Ronnie, The New York Times, May 27, 1984

2. ibid.

3. Grumet, Robert S.1995 Historic Contact: Indian People and Colonists in Today’s the Northeastern United States in the Sixteenth Through Eighteenth Centuries. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

4. (Tooker, William Wallace 1911 Indian Place-Names on Long Island. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, New York.

5. Wick, Steve, Newsday, Sept. 9, 1990 “Fortifying An Indian Culture In Southold”

6. O’Callaghan, Edmund B., editor 1849-51 Documentary History of the State of New York 4 vols. Weed, Parsons, Albany, New York.

7. Solecki 1948 and Williams, Lorraine E. 1972 Fort Shantok and Fort Corchaug: A Comparative Study of Seventeenth-Century Culture Contact in the Long Island Sound Area. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation on file in the Department of Anthropology, New York University, New York.

8. Fort Corchaug Archaeological Site National Historic Landmark Ralph S. Solecki Department of Anthropology, Texas A & M University, College Station, Texas Lorraine E. Williams Bureau of Archaeology and Ethnology, New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, New Jersey 1998

9. 1985 Recent Field Inspections of Two 17th-Century Indian Forts on Long Island. Forts Massapeag and Corchaug. Bulletin and Journal of the New York State Archaeological Association 91:26-31.).

10. McQuiston, John T. 1997 Sale of Indian Fort on L. I. Preserves a Piece of History. Long Island Newsday, July 3, 1997.