In 2018, June Metzner, who was a member of the original “Old House Society” (formed after the original 1940 restoration of the Old House), inspired the members of the Council to embark on a project that would make the interior better reflect 17th-century life. To accomplish this, the Council formed the “Old House Committee.” Grants from The Century Arts Foundation, Robert L Gardiner Foundation, and The Gerry Foundation enabled the committee to start restoration and restaging.

The Council relied on extensive research for authenticity to ensure the interpretation was as accurate as possible. It was determined that the era be informed by primary documentation, scholarly expertise, and scientific analysis.

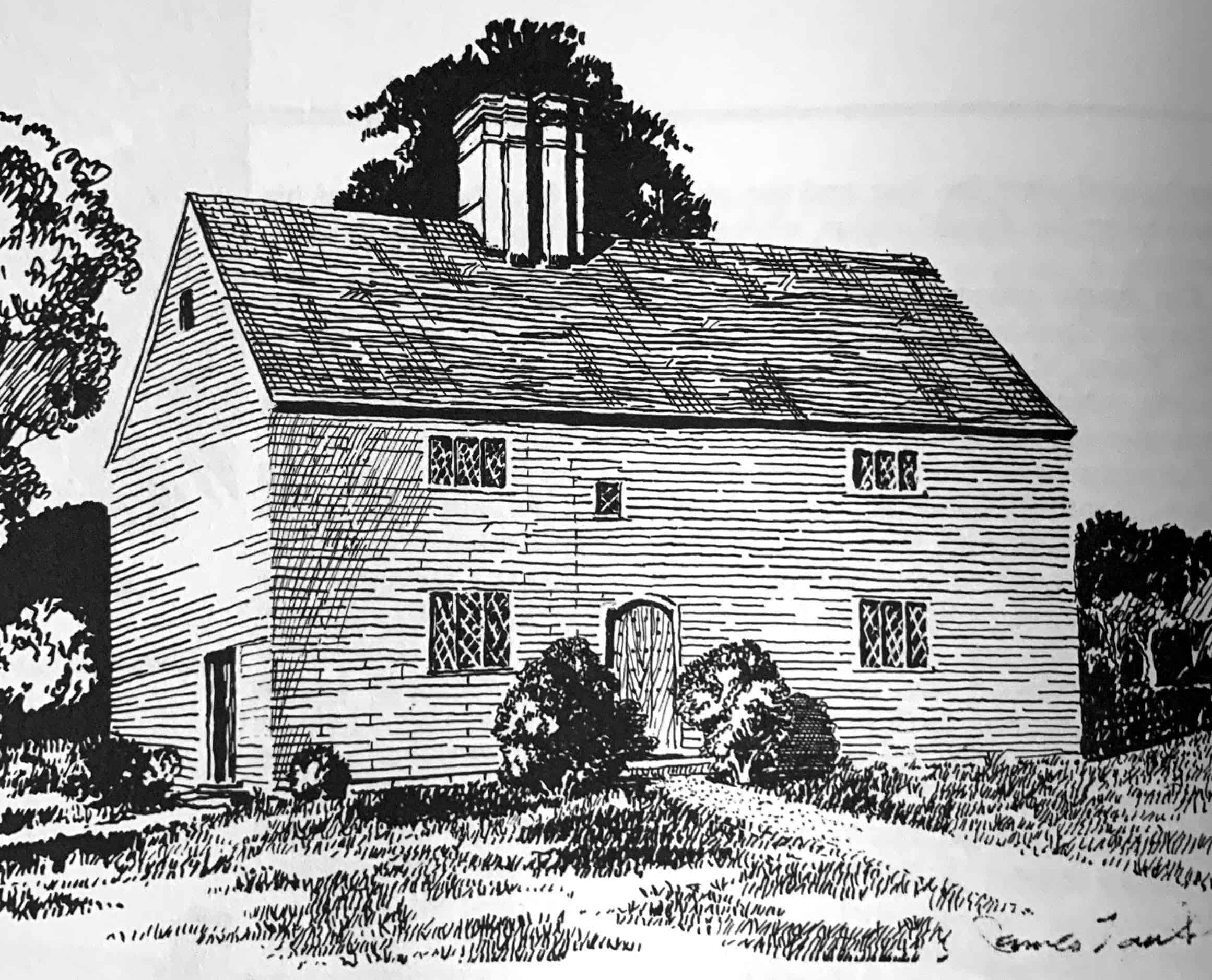

In 2008 a Dendrochronology study showed the wood from the house was felled in 1698. In 2018, William Flynt, an architectural conservator, repeated this testing on 15 core beams, a stud, and a brace. The conclusion was the same as the 2008 study; the trees were felled in 1698, and the house was built on or after that date. All the academic scholars sourced to prescribe appropriate furnishings would use the 1698 date based on this study.

To further ensure we were using the correct date, there was a search of primary documents that would either confirm or dispute it. The search produced only one item, the 1699 deed of sale from Benjamin Horton to Joseph Wickham. The deed spells out the boundaries of the land but makes no mention of a house being on the property. Additionally, an archeological dig did not uncover any 17th-century artifacts. Although research is still ongoing, it was decided that 1698 would be the date used to inform the restaging of the house’s interior. This origin date would become part of the Old House’s history until proved otherwise.

Once the era date was established, John Fiske, author of the book “when Oak was new: English furniture & Daily Life,” began purging items that were not period correct. The committee decided to forgo antique acquisitions for staging because of their cost and rarity. Instead, the House would be a mixture of authentic reproductions and antiques to make the house an interactive experience for the visitor.

The interior is now furnished to reflect the lifestyle of Joseph Wickham, who, in 1698, was a wealthy tanner. Robert Trent, an expert on first-period furnishings, oversaw the restaging. Many reproductions were handcrafted by Peter Follansbee, a nationally renowned woodworker, using pre-colonial techniques and materials and thorough research to ensure authenticity.

The bed textiles were handwoven by Rabbit Goody, a historical textile expert who also used pre-colonial techniques and materials. The current staging of the bed is comparable to an exhibit in the Metropolitan Museum of History American wing.

Electricity was installed to enhance exhibit space, and an interactive sign in front of the building permits disabled visitors also to experience the interior.

Passive climate control displays were installed to preserve the Poppet dolls found during the 1940 renovation, and Barnabus Horton’s cane bequeathed by his family is on display. The poppet dolls were an example of the “magical thinking” pervasive at the time and were meant to keep witches out of the house. The display includes witch bottles and an iron horseshoe; both meant to ward off witches.

Watch the video below for more background information on the old house and details about how and why the restaging was done.